The earliest evidence of modern humans in Europe has been unearthed in a cave in southern France, showing they lived there at the same time as Neanderthals — something long suspected but never established before now.

The findings at Grotte Mandrin, a cave in the Rhône Valley about 80 miles north of Marseille, focus on a single Homo sapiens tooth and on distinctive fragments of flint points that are thought to be for the arrows and darts used for hunting by early modern humans.

The discoveries push back the earliest date of our species — Homo sapiens — in Europe by roughly 10,000 years, to about 54,000 years ago, according to a study on the findings published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

The study also suggests the modern human group was part of an incursion from the eastern Mediterranean coast that didn’t last long before they again vanished from Europe — one of the early waves of Homo sapiens migrating to the continent. They may have numbered a few hundred, including women and children.

“It’s a real group, making an attempt at a real colonization of Western Europe,” said Ludovic Slimak, a paleoanthropologist with the French scientific research agency CNRS at the University of Toulouse and one of the lead authors of the study.

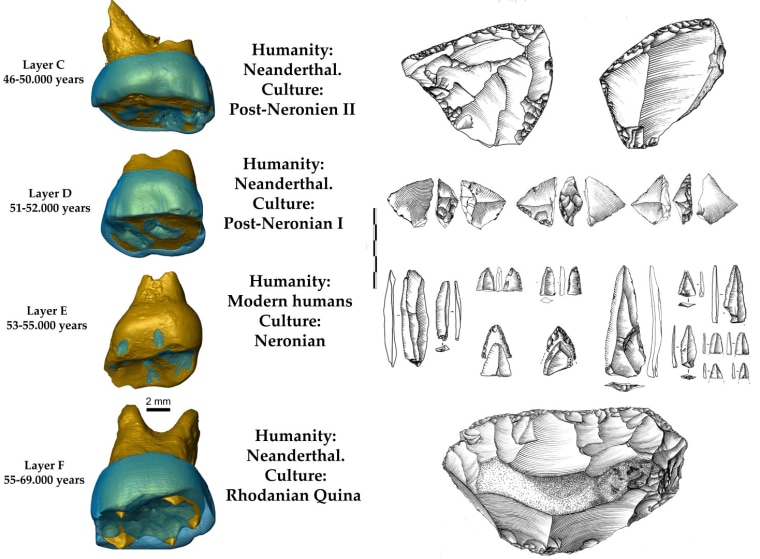

The clearest evidence is a single baby tooth from a modern human child, aged between 2 and 6, that was found in a layer of clay and sand sediments on the floor of the cave.

It was sandwiched between sediment layers that held Neanderthal teeth, among other remains; and because Neanderthals — Homo neanderthalensis, an earlier human species — and Homo sapiens had distinctly different teeth, the evidence is unquestionable, Slimak said.

Analysis of the soot on the cave’s ceiling can be matched with the remains of fires in the sediments and suggests Grotte Mandrin was first occupied by modern humans perhaps a year after it was abandoned by Neanderthals, he said.

It’s not known, however, just why the cave and its surrounding territory changed hands between the two species, and the researchers have found no direct evidence that they interacted. But flints in the modern human layer came from many miles away, so it seems they were familiar with the area’s resources and may have had Neanderthal scouts or contacts, Slimak said.

Slimak has pieced together the story of Grotte Mandrin in his work there over more than 30 years. The Rhône Valley is rich in prehistoric sites, and Grotte Mandrin is one of the most important. Hundreds of thousands of ancient bones and stone artifacts have been discovered in the cave since its discovery in the 1960s, covering more than 80,000 years.

Radiocarbon analysis and luminescence dating established that the modern human layer in Grotte Mandrin is between 51,700 and 56,800 years old. That’s roughly between 10,000 and 12,000 years before the previously accepted date for our species to have first set foot in Europe. Before this, the earliest firm evidence was ancient teeth from Italy and Bulgaria, which are between 43,000 and 45,000 years old. (A fossilized skull from southern Greece may be over 210,000 years old, but it’s disputed whether it came from a modern human.)

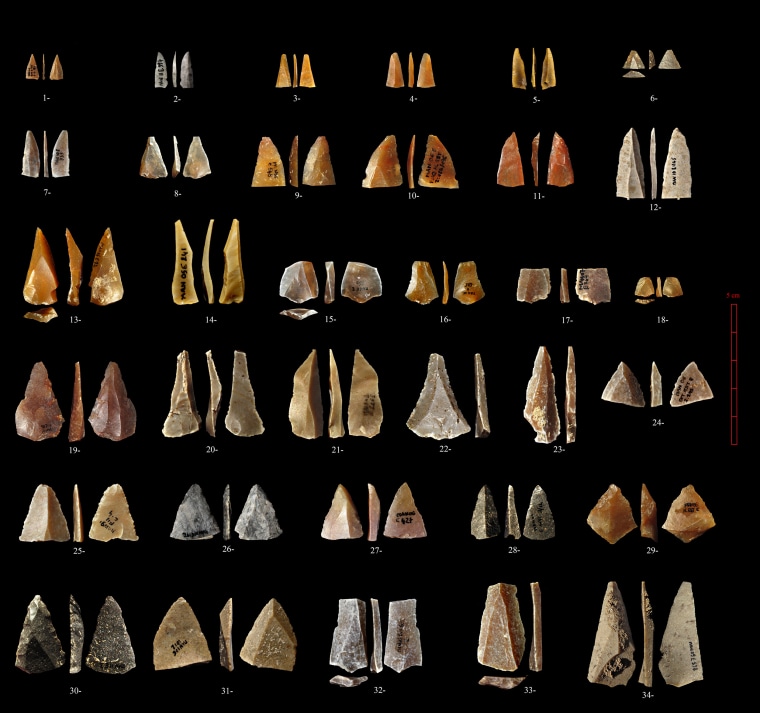

The latest study also examined dozens of flint points found in the cave sediments, which are thought to be from the heads of arrows and the darts used in spear-throwers, or atlatl — devices used for casting small spear-like projectiles. The points were made with the distinctive flint-knapping techniques called Neronian after the Grotte de Néron, where they were first found, about 30 miles north of Grotte Mandrin.

Before now, it wasn’t known if Neronian points were made by Neanderthals or modern humans. But the latest study indicates they are identical to flint points made by early modern humans in Lebanon, so it’s likely the Neronian points were also made by modern humans, Slimak said.

Because Neronian points are only found in the Rhône Valley and in the eastern Mediterranean, Slimak speculated that the people who made them arrived in the Rhône Valley on boats.

He noted the Rhône is one of the Mediterranean’s largest rivers and that the occupation of Australia by modern humans in boats occurred at the same time.

“It is very likely that these navigation technologies were at this time well known by all of these Eurasian modern populations,” he said.

David Strait, a professor of biological anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis who wasn’t involved in the study, said the discoveries are the best evidence yet that Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted in Europe at times, until modern humans became the only species there about 39,000 years ago.

DNA analysis shows Neanderthals interbred with modern humans, but it’s not known just when. The new finds raise the issue of whether they interbred at this time, or if they did not despite having the opportunity to do so, he said in an email.

“With luck they will discover more fossil humans that might shed light on these questions,” he wrote.

Paleoarchaeologist Gilbert Tostevin, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Minnesota, noted the Neronian points didn’t influence the Neanderthal points found in later sediments at Grotte Mandrin.

“This is another indication … that the modern human disposition into Europe should not be seen as a huge wave that swamped the local Neanderthals but as a series of successive, smaller waves of moderns that led to the replacement of Neanderthals,” he said in an email.